Our Framework: Bullish on the Economy

As Omicron loosens its grip on the US, it’s been nice to resume a more normal routine, including returning to the office full time and getting back on the road for business travel. Zoom is incredibly effective, but virtual meetings aren’t a perfect substitute for the real thing. I missed the spontaneous interactions with colleagues, from which some of our best and most creative ideas take seed. And I missed meeting with clients and our organic conversations, complete with a handshake, or at least a fist bump.

Recently, I was fortunate to speak at conferences in Miami, Las Vegas and the Rockies, and to participate in smaller group and one-on-one client meetings. In this month’s essay, I highlight key points from those revealing discussions and focus on the aspects of the economy that raised the most questions; namely, equities, bonds, housing, and the economy’s debt burden against the backdrop of rising rates. I want to thank everyone who took time out of their schedules to meet. We are better when we are together and—finally—in person.

When Byron and I drafted this year’s Ten Surprises, we wanted to convey our optimism on the US economy while also acknowledging that market conditions would be more difficult. In our first Surprise, we wrote that earnings would collide with higher interest rates, resulting in greater volatility and a challenging outlook for forward returns across many asset classes. We expect economic growth to maintain strong momentum this year, but rising rates will challenge investors and policymakers alike. This theme underscores many of this year’s Surprises.

The fiscal response shouldn’t be underestimated Our bullishness on the US economic outlook is based on the historic $6 trillion fiscal response to the pandemic. In effect, in just a matter of months, policymakers airdropped approximately 30% of 2019 GDP into the economy, roughly equivalent to the economies of California, Texas and Florida combined.1 We haven’t seen fiscal expansion like that since the New Deal Era nearly a century ago. As one result of an unprecedented coordination of fiscal and monetary policy, the Federal Reserve more than doubled the size of its balance sheet to nearly $9 trillion.2 Now, the economy faces the unintended consequences of this grand experiment, including inflationary pressures and supply chains overwhelmed by stimulated demand.

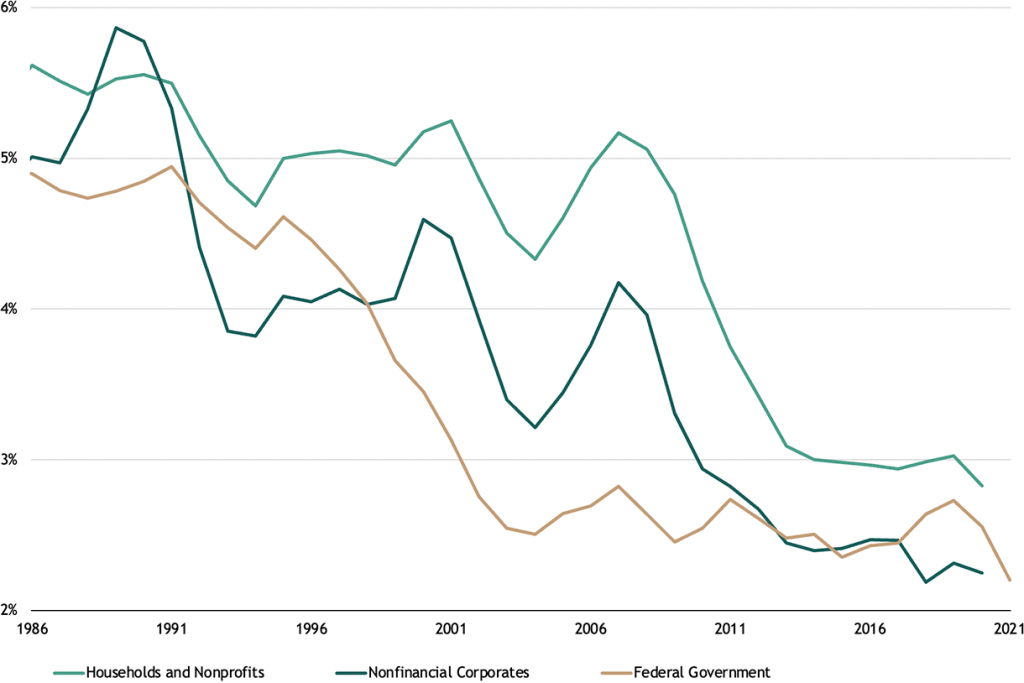

Deep pockets can mitigate recessionary risks All the newly printed greenbacks won’t simply vanish. When the service side of the economy revs up, as we expect it will this year, consumer spending will get recycled again and again in the economy. This dynamic is largely in contrast to goods consumption, where spending is often exported to the lowest-cost producer globally. As spending shifts from goods to services, it will alleviate much of the “transitory” supply-side inflation evident in the economy.

But, for every action, we should expect an equal and opposite reaction, and we are likely to see demand-side inflation pick up. We’re already seeing it in wages and rents. But this is the type of inflation that the Fed, by tightening monetary policy and dampening aggregate demand, is more able to affect. Despite the near-certainty of higher interest rates, I expect the padded wallets of US consumers, corporations, and state and local governments will create a virtuous cycle that proves to be enormously valuable in dampening recessionary risks.

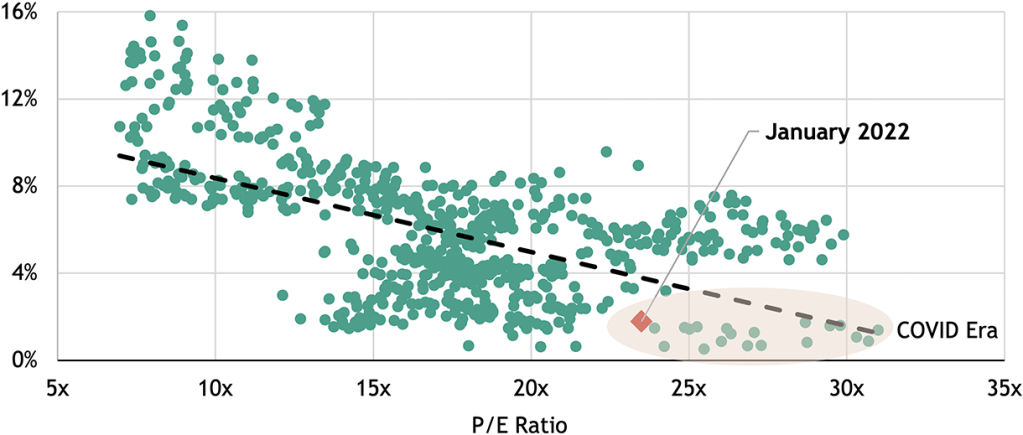

Duration risk the biggest challenge for investors We also think the 10-year Treasury yield will rise to 2.75%. This Surprise remains significantly out of consensus. Yet the last time inflation was at 7.5%, the 10-year Treasury yield was at 14%.3 While it’s unlikely that we’re in a 1980s redux, history suggests that the current 10-year yield is not appropriate in today’s economic context. When the Fed ceases Treasury purchases and begins to reduce its balance sheet, I expect price discovery will return to markets. A higher, more realistic level in long-term rates is likely to ensue.

I think this dynamic is the biggest challenge that investors face right now when they think about asset allocation. Higher long-term rates equate to duration risk—which isn’t limited to fixed income. Virtually every asset in a portfolio, equities included, has some sensitivity to increases in interest rates, which is the basic definition of duration. Managing this duration risk will be critical. Allocators of capital must consider many paradigms when they build a portfolio. But in this rising rate environment, I believe one of the most important things they should do is to evaluate every holding through the lens of whether it can hedge against or benefit from a higher 10-year Treasury yield.

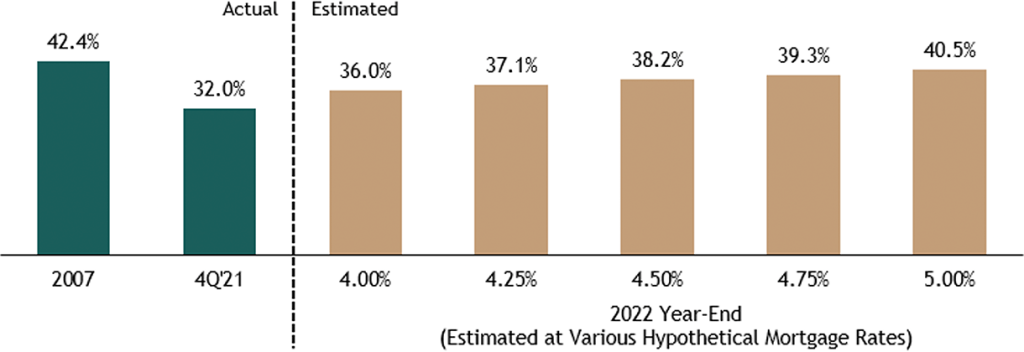

As the threat of higher rates settles in, questions about equity market performance, risks to traditional bonds, housing and the economy’s debt burden have dominated my recent conversations with clients. And I expect that they will continue to do so throughout 2022.